On Christmas Eve in 1978, I quietly slipped away from the dinner table and made my way to the dimly lit parlor. The bank of windows facing the sidewalk showcased the twinkling lights on the houses that lined Richardson Street. This formal room was reserved for Christmas, Easter, and the occasional visit from Sister Marie James. Sitting down cross-legged on the worn oriental rug, I watched the sparkling lights from our Christmas tree as they danced about the room, casting a colorful, magical glow on everything. From the kitchen, I could hear the excited voices of my brothers and sisters, combined with the clinking of glasses and silverware. Filled with a sense of wonder, I sat contentedly in the near darkness. With my face close to the sweet, sappy scent of the balsam pine, I brushed a few stray needles from the top of a brightly wrapped gift. Peeking under the ribbon, I was able to sneak a glance at my name on the tag. The package was perfectly square, about twelve inches on each side. I balanced it on the palm of my hand, assessing the content. I didn’t think I’d be able to sleep that night from the anticipation.

Being the youngest of nine children, I sometimes felt lost in the crowd; but I certainly never felt alone. I will never know how we all managed to cram into the downstairs apartment of my grandparents’ house. It was a 1930’s Craftsman home, with hardwood floors, classic wood trim, and solid wood doors. My grandparents’ apartment upstairs still had the original antique glass doorknobs, which I had once thought were diamonds. The built-in china cabinet in the dining room was my bureau. Oftentimes I would sneak into the parlor and cram into my favorite spot behind the couch, near the warm steam radiator. Oh, the hours I spent watching the cars go by and the clouds moving across the sky. One might even say I was a bit of a daydreamer. In my little hideaway behind the sofa, I was able to find my own space; It was not tangible or physical, but it was vast and limitless. When gazing at the sky, or reading my books by the old radiator, my thoughts and emotions found their own way to the surface, like weeds pushing through the cracks in the sidewalk. At this particular time of year, the Christmas lights dancing around the room made my dreamy hours feel all the more enchanting.

On Christmas morning, while the others still gathered around the tree, I once again slipped away to the privacy of the empty girls’ bedroom. In my folded arms, I clutched the object of my desire. I can’t remember anything that matched the excitement of opening a new record. Tearing the cellophane wrapper off, I gently removed the coveted circle of vinyl from its sleeve. The cover featured a young man with a trumpet; he was leaning against a dingy wall in New York City. Looking into his eyes, I felt a loneliness, a need to be understood. Although we had never met, we were connected by his music. Switching the knob on the turntable to the 33 rpm position, I placed the needle on the third song. I would play it over and over that day before I moved on to the other songs.

With the room to myself, I began singing along, using a hairbrush for a microphone.

“I don’t need you to worry for me ’cause I’m all right…”

“My Life” was the number one song on the pop charts the week of December 23rd, 1978.

“I don’t need you to tell me it’s time to come home.”

That Christmas afternoon, I dreamily lay in my bottom bunk oasis for hours, listening to and learning the words to every song on Billy Joel’s 52nd Street.

“I don’t care what you say anymore, this is my life.”

Forty-five years later, it still stands out as my most memorable Christmas.

“Go ahead with your own life. Leave me alone.”

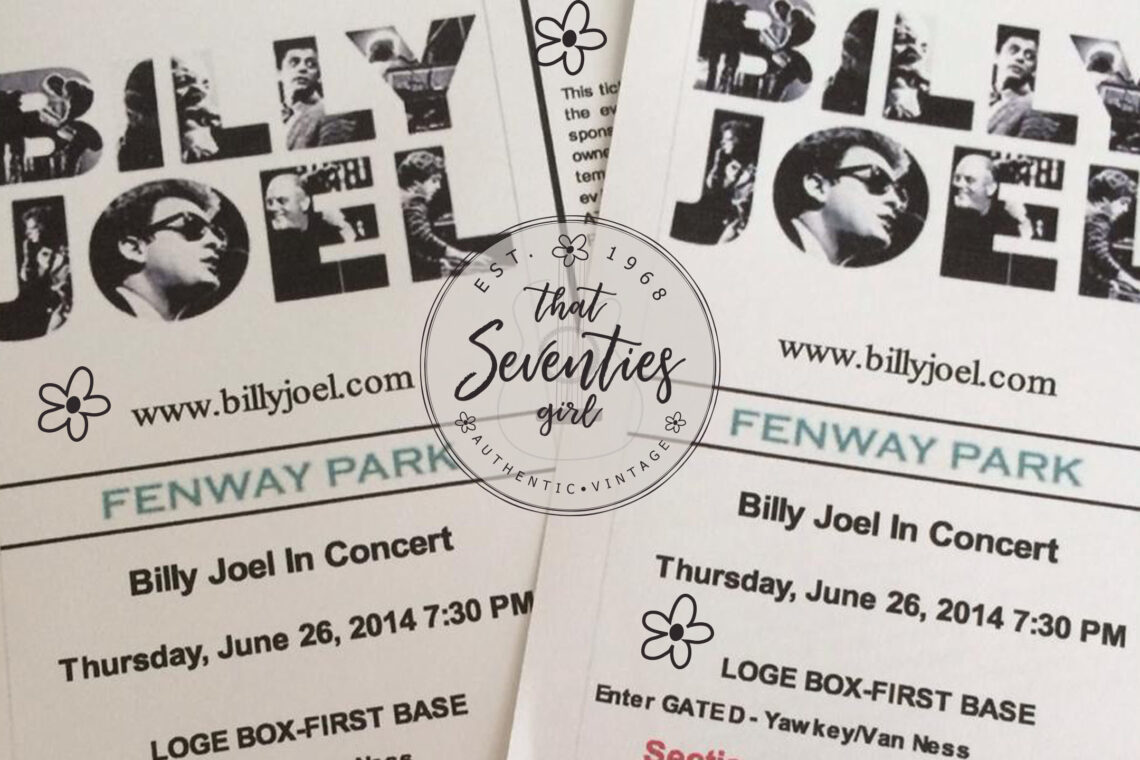

On the day she got married in 1974, my sister Regina moved out. I had been the flower girl at her wedding. I still remember my pretty dress, with the puffy sleeves and white embroidered daisies. On Friday afternoons, she often stopped on her way home from work and brought me to her place. I so enjoyed those nights at my sister’s apartment. Her husband, Charlie would fall asleep, while we sat up for hours watching movies, talking, painting our nails, and listening to her records. After she was asleep, I would plug the headphones into her stereo system and play her records for as long as I could stay awake. Shortly after that Christmas in 1978, came the night I discovered a copy of Turnstiles in her collection. I loved listening through the headphones because it allowed me to better distinguish the different sounds and instruments in the music. This is the way I heard “Say Goodbye to Hollywood” for the first time. The drum beats at the beginning drew me in immediately. Thirty-six years later, I was to hear that drum intro ricocheting through Kenmore Square in one of Billy Joel’s Fenway Park appearances. A smile would break out across my face, as I remembered my ten-year-old self, sitting cross-legged on the floor next to Regina’s couch that night in early 1979. That little girl would squeal with delight if she could “see me now”, standing there in America’s oldest ballpark in July of 2015, with happy tears rolling down my cheeks.

“Wha-ah-oh-oh-ohhhhhh”

I turned twelve years old in January of 1980, around the time Glass Houses came out. I think I may have driven the entire sixth grade crazy singing “You May Be Right” and “It’s Still Rock ‘n’ Roll to Me” on the Noonan School playground, day after day. At overnight camp, I met a girl named Debbie from the Lincoln School downtown. Being the gregarious (if not obnoxious) preteen I was, it didn’t take long for Debbie and me to discover our common interest. We sang the songs from Glass Houses all week, eventually drawing a few eye rolls from the rest of our group; especially one cute Lincoln boy whose name I can’t recall now.

Da da da dah, da da da da dah…

“Friday night I crashed your party, Saturday I said I’m sorry, Sunday came and trashed me out again.”

While the 1970s were making their way into the 1980s, there was someone else enjoying the music of this talented young man from New York. Born in the 1930s, my father was the epitome of a traditional blue-collar, family man. I think he could relate to Billy Joel’s music. This gentle man, who had always considered me to be his little girl, probably didn’t have a clue how to relate to this new, almost teenager, who had taken over my being. The music we both loved developed into a strong point of connection between us. When I played my albums, he would poke his head through the doorway of my room. He’d ask what I was listening to or tell me about a song he’d heard on the radio. It was more about the things we weren’t saying than the things we were saying. When there wasn’t a ton of common ground to be found, music was a link holding us together.

In 1982, when I was a freshman in high school, The Nylon Curtain was released. Being the daughter of a mailman, with eight older brothers and sisters, and being raised in a comparatively wealthy town, I developed somewhat of a chip on my shoulder. While I wore mostly hand-me-downs, my classmates wore designer jeans and wooden clogs. If I wanted these things, I had to buy them myself. I had been working since I was twelve years old, as an assistant at Scruples Hair Salon. The working-class tones of “Allentown” resonated with me. The song reminded me I was not so different from everyone, as I often felt. There was more to the world than the slightly pretentious suburb of Winchester, Massachusetts.

“So the graduations hang on the wall. But they never really helped us at all. No, they never taught us what was real…”

In 1983, Billy Joel moved things in a new direction; or was it an old direction? An Innocent Man was reminiscent of the nineteen fifties, with the Doo-Wop feel of “Uptown Girl” and “For the Longest Time”. That summer, I was fifteen; it was the summer of my first love. My parents, however, were not keen on the relationship: he was older, going off to college in the fall. On our first date, we went to Salisbury Beach with my best friend, Diane, and her (also older) boyfriend, Tommy, who drove a 1972 Ford Mustang; and he drove it fast. The boys drank beer and Diane and I drank Coca-Cola with Bacardi rum. I was dizzy when we rode the upside-down Ferris wheel; I pretended to be a bit more scared than I was because I liked the way it felt when the boy put his arm around me. On the way home, I kissed him in the back seat while we listened to Tommy’s cassette tapes playing through the cranked-up speakers. I will always remember that sweet evening. I asked to be dropped off at the Dairy Barn (a little red barn-shaped store on the corner) where Richardson Street met Main Street. It was way past curfew when I slowly, quietly turned the back door handle hoping to make an escape to my room. My parents were standing there in the kitchen. I was screwed.

On Labor Day, my boyfriend pulled out of the Dairy Barn parking lot in his father’s old silver Dodge Dart and headed off to UMass Amherst. We wrote each other letters almost every day. I would sit on the front steps after school waiting for the mailman to arrive. I slept with the letters under my pillow, counting the days until I would see him again. The weekend of my sophomore semi-formal, he was finally coming home. That Friday, I waited by the phone all afternoon. I would periodically pick up the phone just to make sure there was a dial tone. The hours went by. But he never called. I didn’t want to wait by the phone any longer, so I went out with friends to a house party. The boy was there. He was home, but he had never called me. My heart was broken. After a strong rum and coke and a few hits from a joint that was being passed around, I began to feel a little sick and dizzy. Not wanting to be a drag to my friends, I called home to ask for a ride. I was so relieved when my father was the one to answer the phone. Ten minutes later, my father was there. In the car, there was no lecture about the drinking. “Keeping the Faith” was on the radio. The song reminded him of the days when he and my mother were dating. He spoke of black and white milkshakes and lime rickeys. The music was still the glue, holding us together. He knew I needed his support much more than any lecture. I don’t think he ever said a word about the party to my mother.

I finally got to see Billy Joel live in concert during my freshman year of college. Twice. The first show was in October 1986 at the Centrum in Worcester, Massachusetts. Tickets went on sale months ahead of time through Ticketron (a predecessor of today’s Ticketmaster). On the given date and time, you would have to dial a 1-800 number over and over, usually getting a busy signal. The shows would sell out in ten or twelve minutes. If you were lucky, you got through; the tickets (hard tickets we saved as souvenirs) would eventually arrive via snail mail in a little envelope. It was so exciting to have one of those little envelopes on the fridge, under a magnet or pinned to the bulletin board by the calendar. At that time in my life, my father was battling his first round of cancer. He had been through a pretty rough surgery a few weeks before and was in the midst of a round of daily radiation treatments. Resting on the couch, sipping his never-ending cup of Taster’s Choice coffee, he winked at me as I was heading out the door. He knew how much this meant to me. Although he was weak, his eyes were sparkling with happiness for me.

In March of 1987, my then-boyfriend and I drove to Virginia Beach for spring break. This was before the days of the internet. News didn’t spread the way it does today. When we went out exploring the area the first morning, we drove right past the Hampton Coliseum, where the giant letters on the billboard outside said “BILLY JOEL TONIGHT”. I nearly jumped out of my seat before I noticed the smaller words at the bottom. SOLD OUT. Riding away in the car, I was crushed. It felt like a miracle, or a stroke of luck, or maybe just being in the right place at the right time when, a few minutes later, the radio announcer came through the car speaker with a notice that a limited number of additional seats would be sold for that evening’s show. We were the first people to walk into the box office. The seats were just to the side of the stage. We were in folding chairs, a few feet away from the grand piano and the man sitting behind it. Needless to say, it was better than any Spring Break adventure I could have imagined.

“We Didn’t Start the Fire” came out in 1989 when I was 21 years old. The song reminds me of a sky filled with fireworks or notes coming to a crescendo. My father and I shared a great appreciation for history, so it didn’t go unnoticed by either of us how Billy Joel managed to squeeze so many years into this power-packed song. My father was duly impressed; I remember him talking excitedly about the song, as we sat in lawn chairs on the beach. Our relationship had survived my tumultuous teens, leaving us with a residual friendship to be compared to none.

Twenty years later, on a warm, breezy summer afternoon in Maine, my father and I sat facing each other in the lawn chairs again. His face was pale from the rounds of chemotherapy he’d endured. For the first time in my life, I saw an unsettling frailty about him. I knew our days together were coming to an end.

To be continued…